The five wall-mounted assemblages comprising 56 Henry’s Laurie Simmons exhibition, DEEP PHOTOS / IN THE BEGINNING, are in keeping with the artist’s career-long interest in figurines, dolls, American kitsch aesthetics, and Cold War era suburbia. The series’ novelty is in Simmons’s use of medium-sized box constructions, a turn away from photographing enclosed vignettes. In the late 1970s, she worked as a commercial photographer, shooting Shackman dollhouse furniture and working with incongruently scaled items. Simmons’s early series, such as “Color Coordinated Interiors” (1983) and “Early Color Interiors” (1978–79), were directly informed by this commercial work. She photographed brightly colored plastic housewife figurines posited in modestly decorated, and sometimes chromatically overlit, middle-class interior rooms, oft charting “women’s work” (e.g., cleaning, cooking). The more recent variation in media—that is, Simmons’s transition from slanted photographic images to the three-dimensional “Deep Photo” assemblages—transmogrifies the camera’s perspectival manipulation to the percipient’s viewing activity.

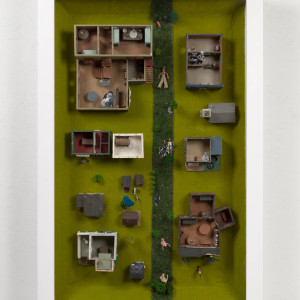

Laurie Simmons, Deep Photos (Cowboy Town), 2021. Plywood, teak, pine, plastic, paper, synthetic grass, metal, hot glue, acrylic paint, fabric, stone, glass, 60 x 40 x 8.75 inches. Courtesy the artist and 56 HENRY, New York.

The resulting effect allays the uncanny that has charged much of Simmons’s oeuvre and stokes a more latent voyeurism. In most of the works, we view the “Deep Photo” assemblages from a bird’s eye view. In Deep Photos (Cowboy Town) (2021) and Deep Photos (Deluxe Redding House/Dream Kitchen) (2023), the roofs of her structures are peeled away, revealing floor plans and unsealing interior lives. The eponymous figures of Cowboy Town lay embowered by bushes and trees dotting a verdant strip that bisects two queues of roofless houses. In Deep Photos (Sparkle House) (2022), Simmons retains the roof but removes the outward-facing wall to reveal the levels of a two-bedroom family home, its sole occupant a miniature housewife perched on her bed. Elsewhere, as in Deep Photos (Mekong Delta) (2021), a Vietnam war scene of cantoned ships, tank traps, and a cadre of UN nurses donned in blue dresses make up the mise-en-scene. There is little that is scandalous in these unveiled private lives. Neat rows of mustard-yellow, cherry-red, and baby-blue furniture and checkered tile flooring aptly match our collective fantasies of mid-twentieth century American suburban life.

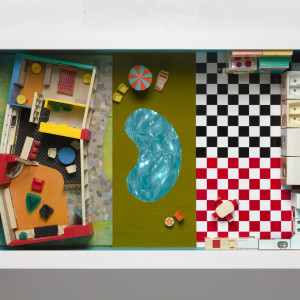

Laurie Simmons, Deep Photos (Deluxe Redding House/Dream Kitchen), 2023. Plastic, paper, acrylic paint, super glue, hot glue, epoxy, metal, plexiglass, 40 x 60 x 15 inches. Courtesy the artist and 56 HENRY, New York.

In some of the “Deep Photos,” an incompleteness betrays the “built” quality of the vignettes. Sparkle House’s upholstered fabric lining is not evenly dispensed across the walls’ expanses. Redding House’s bean-shaped Plexiglas—indexing a swimming pool framed by saffron-yellow lawn chairs—is curiously offset by an open kitchen plan (fixed with a dual set of identical sinks). The gleam of artificially lit plastic furniture that often colors Simmons’s earlier photography of dolls in rooms carries over to these tawdry, kitsch schemas.

Simmons makes use of what Lucy Lippard called “down” images in her 1973 Ms. article, “Household Images in Art.” Lippard had in mind Marjorie Strider’s high-relief “build-outs” of freestanding dustpans, baking soda boxes, and brooms erupting from cobalt polyurethane foam. Simmons instrumentalizes such items to allocate suffocation by, as Lippard described it, “[domestic] things that are too familiar.” For Simmons, this is not necessarily a semiotic endeavor. Unlike her fellow Pictures Generation artists, she is not a politicized post-modernist displacing images from their commercial settings to decontextualize them and reveal an ideological purport. Rather, she displaces various constituent miniatures and figures—some mass-produced and others artisanal—from their original built environments only to posit them in different built environments. Like her Pictures Generation colleagues, Simmons is a collagist. Yet her modules are not outward-pointing, their anchoring not in a recognizable media lexicon but a general, imaginary ethos. It would even be unwarranted to say that this series takes the regime of the male gaze as its target, though a particular masculine-coded imaginary—composed of genre-based visual leitmotifs including cowboys, pin-up dolls, and Vietnam War action figures—subtends Simmons’s world-building. Granted, she does exact self-referential cues in several works. In Deep Photos (White House Green Lawn/Swimming Pool) (2024), the titular “White House” includes a background photograph from her 1984 “Fake Fashion” series. But this recycling is mostly incidental to what her “Deep Photos” are about.

Laurie Simmons, Deep Photos (Sparkle House), 2022. MDF, paper, metal, plastic, cardboard, wood, fabric, battery, led lights, marmoleum, hot glue, acrylic, sand, stone, plexiglass, 60 x 40 x 24 inches. Courtesy the artist and 56 HENRY, New York.

The “Deep Photos” embody their “aboutness” in how the formal aspects of the box-based constructions guide our reception of visual data, hewing closely to the contained cosmologies of Joseph Cornell, Dan Basen, Wayne Nowack, and Arman. Simmons reveals and occludes parcels of domestic imaginary, using the miniature room—itself a gendered vessel due to its contiguity to the dollhouse—to augur our partially obstructed bird’s eye access. These rooms delineate how oblique access conditions a totalizing worldview, unspooling at the seams when confronted head-on—hence the unevenly dispensed wallpaper and embroidery. Simmons’s constructions, when viewed up-close, reveal nail heads, blemishes, and incongruities.

This is related, though not equivalent, to what Leo Steinberg, in Other Criteria (1972), called the “flatbed picture plane”—the postmodernist visual device that “no more depend[s] on a head-to-toe correspondence with human posture than a newspaper does.” According to Steinberg, the emergence of the “flatbed picture plane” is coeval to a turn away from images that harken back to the natural world of sense data—i.e., nature “experienced in the normal erect posture.” For Steinberg, the modernist canon, ranging from Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) to Morris Louis’s “Unfurled paintings” (1960–61), produced images optically relative to the columnar body. Robert Rauschenberg and Jean Dubuffet upended this, painting “opaque flatbed horizontals” that symbolically alluded “to hard surfaces such as tabletops, studio floors, charts, bulletin boards—any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered.” Simmons similarly scatters objects—albeit, three-dimensional ones—across such “receptor surfaces.”

Notably, Steinberg deemed the visual experience of the “flatbed picture plane” an “operational process” where the array of heterogenous objects horizontally viewed indicates a “shift from nature to culture.” It is precisely “culture” with which Simmons’s “Deep Photos” is concerned. Unlike the “flatbeds” of Rauschenberg and Dubuffet—paintings whose flat surfaces served as repositories for (flat) painterly information—Simmons makes good on the flatbed’s intrinsically “operational” essence, forcing us to rotate our necks, peer under roof beams, and trace wall seams. This act of ceding and taking optical information reveals the shakiness of the built environment, of a piece with the prefabricated cultural imaginary that Simmons tactfully fashions in her “Deep Photos.”

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..