“Uncanny,” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, mines the anxious terrain of flesh, robots and off-kilter realism.

“I have deep feelings,” says a woman whose blank stare seems to indicate otherwise. She’s a humanoid robot named Bina48 who has realistic latex skin, stiff movements and a lilting, mechanical voice. And she’s staring into the eyes of another woman, artist Stephanie Dinkins.

Some people think her feelings are a simulation, “and I find that deeply offensive,” says Bina48 to Dinkins in the 2018 video “Conversations With Bina48: Fragments 7, 6, 5, 2.” “You’d have to lack all empathy to not accept my feelings, which would make you kind of a monster, actually.”

The narrow gulf between human and monster is called the uncanny valley, and its topography is the subject of the exhibition “Uncanny” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. That term was coined in 1970 by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori, who hypothesized that there is an “uncanny valley” — a nonlinear representation of the relationship between robots’ human resemblance and likability. (We like humanoid objects up to a point, but when they cross a threshold of realism without actually being real, we find them repulsive.)

But the notion of the uncanny dates back farther than that: In 1919, Sigmund Freud described it as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” It’s “an anxious uncertainty about what is real caused by an apparent impossibility,” wrote Mark Windsor, a British philosophy scholar, in the British Journal of Aesthetics 100 years later.

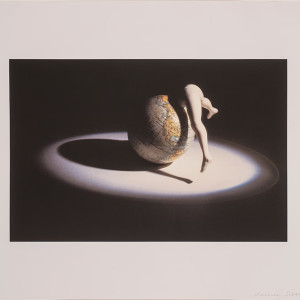

It’s rich psychological terrain that encompasses dolls, mannequins, ventriloquist dummies, robots, corpses, mirror reflections and any other humanlike figures or their parts that give you a pit in your stomach or a creeping feeling up the back of your neck. You’ll get it several times throughout the exhibition — maybe at Valeska Soares’s untitled sculpture of realistic mouths, complete with teeth and tongues, made out of beeswax, or “Limp,” her extra-long latex hand and leg combo limb. Or maybe at Louise Bourgeois’s “Untitled (With Foot),” a sculpted pink marble sphere with a baby’s foot protruding from underneath, on a marble plinth that reads, “Do you love me?” Or maybe the lifelike masks of Gillian Wearing, whose name is in this case an aptonym.

Because women are conditioned by society to make others feel at ease, a woman’s desire to make someone feel uncomfortable can be seen as an aggressive act. Creating unsettling art is a way, then, of reclaiming power through confrontation. There can be an uncanny horror in stifling domesticity, as explored in Laurie Simmons’s photographs of dolls, or in Frida Orupabo’s collages about childbirth, in which a post-C-section baby with an adult face makes direct eye contact with the viewer.

But the term should not be a catchall. Some of the works in the exhibition that focus on places or surrealist images are mysterious or mystical or unsettling, but not quite uncanny. It’s only when you get into human forms, or representations of them — like Justine Kurland’s photographs of schoolgirls so placid they could be corpses, or Mary Ellen Mark’s photographs of twins (back to Freud: doppelgängers) — that the feeling returns.

Perhaps the most uncanny space in the exhibition is an installation by Mathilde ter Heijne, “F.F.A.L. #1, #2, #3” (it stands for “Fake Female Artist Life”). In a three-sided room, three life-size, elegantly dressed mannequins stand motionless, staring at the viewer. They represent three fictional female artists from literature: Elvire Goulot (“La Femme Assise,” by Guillaume Apollinaire), Elaine Risley (“Cat’s Eye,” by Margaret Atwood) and Ueno Otoko (“Beauty and Sadness,” by Yasunari Kawabata). Piped-in audio allows them to “speak” fragments of lines from their stories: “But these I found quite repulsive … I have no idea of the face and form of the … only [of] a vision in my heart …”

It’s their size, their realistic skin and their vacant, dead eyes that make this space the most viscerally uncomfortable in the exhibition. Especially when you stand right in between them.

Imagine doing it all day long.

“I’ve gotten used to them,” said a museum guard, asked what it was like to be in their presence all day. “But one day, when the light was dimmer …” She mimicked herself doing a double take.

National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1250 New York Ave. NW. nmwa.org. 202-783-5000.

Dates: Through Aug. 10.

..

..

..

..